Dear I Fly at Night,

My question is: Do you wish more people shared their concern with you about your drinking?

I have worried about an extended family member’s drinking for many years. This family member is functional but drinks far more than is healthy. This person is also very defensive (in general), and I do not think they would be open to hearing concern from me or anyone else. I fear that I do not have enough ‘evidence’ (I know that is a terrible word) to support that this person’s drinking habits are bad, and I worry that the conversation would ruin a relationship since I think concern will just be denied. I also know other family members are worried but share my same concerns about having a discussion. Is this a better conversation for a closer family member to approach? Or should we wait until this person reaches out to us? Do people now ever say to you how worried they were, and you wonder, ‘well, why the heck didn’t you say something?!”

Sincerely,

Concerned Family Member

Dear CFM,

I’ve been asked this question by friends who wonder if they should’ve known more about my situation (“I feel like I should’ve seen it”), by people who did see it and wonder if they should’ve said something (“I feel terrible now that I didn’t say anything – would it have made a difference?”), and by strangers who are worried about someone, like you.

I have to say, I’m anxious to answer because I’m not a doctor, nor am I trained in psychology, interventions, or anything like that. I only have my own experience. That said, I do have my own experience and I’ve spent a lot of time with addicts, alcoholics and their loved ones, and I’ve heard hundreds of people ask and answer your question.

The short answer is yes. You can and should say something.

The long answer is as follows.

You asked if I wonder why more people didn’t say something. Yes and no. I don’t blame anyone for not broaching what was only sometimes obvious and a really tricky subject. I don’t blame anyone for anything, really. I do appreciate every person who did say something, even if I hated their words at the time.

There were five people in my life who pointedly expressed concern, two who gave me ultimatums. This is what they said:

“Drinking seems to have a deleterious effect on you, honey. You don’t need it.” – Friend, at his kitchen table, a year before I stopped.

“You can do with this what you will, but I need to say it because I’m your father. Your relationship with alcohol is not healthy.” – Dad, on the phone, a few days after we had a few drinks together in Boston and shortly after my DUI (which he learned about just before calling).

“Stop fucking drinking, Laura!” – Husband, the morning after I’d picked a fight with him (again).

“You should not have driven last night. If it doesn’t slow down, I can’t hang out with you when we’re drinking any longer.” – Best Friend, a couple years ago. This wasn’t the first time she’d expressed concern, the tone was uncharacteristic and warranted and I knew, backed by immense care and concern.

“You are not someone who can drink, Laura. Some people can. You can’t. If you keep going you are going to lose everything. Including your daughter. I will make sure of it.” – Brother, after the bottom night I wrote about previously.

It’s important to say all these people were my drinking buddies. It’s also important to note none of the conversations made me stop drinking, but all of them gave me pause, and the last two stopped me in my tracks hard. I stored the words. I stored all the words people said over the years, even if I didn’t want them, even if I scoffed and got defensive or laughed them off. I could always point to someone far worse, or to ways I could control my drinking, because right up until the end I could if I was trying to get the heat off. Addiction hardly ever looks like the brown paper bag version of a bum we see on the street; it’s far more often the faces around us every day – people who appear to be holding it together. “Functional,” as you said, even thriving.

All these conversations took place in the last years of my drinking. Before that, I blended in for the most part (this will make some of my friends laugh – they will assure you I did not blend in!) but I can tell you I was in trouble long before. I was in trouble from the beginning. If you are concerned, CFM, you need no further evidence. Don’t wait until you have more. I imagine the evidence you do have is 1/100th of the full case, even if they can’t see it themselves.

I’m currently re-reading Stephen King’s exquisite memoir On Writing. In it, he recounts the intervention his family staged when it was clear he wasn’t responding to their less severe pleas. I’m going to cite a pretty long passage because it includes so many juicy, telling bits. Plus, he’s just a freaking master.

“Not long after that my wife, finally convinced that I wasn’t going to pull out of this ugly downward spiral on my own, stepped in. It couldn’t have been easy—by then I was no longer within shouting distance of my right mind—but she did it. She organized an intervention group formed of family and friends, and I was treated to a kind of This Is Your Life in hell. Tabby began by dumping a trashbag full of stuff from my office out on the rug: beercans, cigarette butts, cocaine in gram bottles and cocaine in plastic baggies, coke spoons caked with snot and blood, Valium, Xanax, bottles of Robitussin cough syrup and NyQuil cold medicine, even bottles of mouthwash. A year or so before, observing the rapidity with which huge bottles of Listerine were disappearing from the bathroom, Tabby asked me if I drank the stuff. I responded with self-righteous hauteur that I most certainly did not. Nor did I. I drank the Scope instead. It was tastier, had that hint of mint.

The point of this intervention, which was certainly as unpleasant for my wife and kids and friends as it was for me, was that I was dying in front of them. Tabby said I had my choice: I could get help at a rehab or I could get the hell out of the house. She said that she and the kids loved me, and for that very reason none of them wanted to witness my suicide. I bargained, because that’s what addicts do. I was charming, because that’s what addicts are. In the end I got two weeks to think about it.

In retrospect, this seems to summarize all the insanity of that time. Guy is standing on top of a burning building. Helicopter arrives, hovers, drops a rope ladder. Climb up! the man leaning out of the helicopter’s door shouts. Guy on top of the burning building responds, Give me two weeks to think about it.” — Stephen King

I’ll let that speak for itself, but the key phrase in my opinion is “the insanity of that time.” Your loved one isn’t in their right mind, even if they appear functional. That’s what alcohol does. Denial and all that.

|

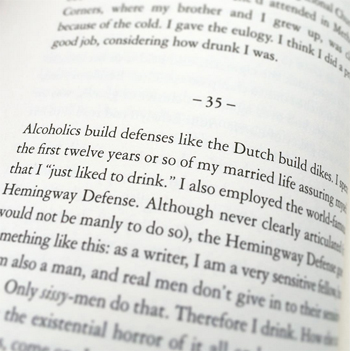

From On Writing: "Alcoholics build defenses like the Dutch build dikes."

The best thing you or anyone else can do before approaching someone is try to understand their frame of mind. Alanon is an incredible organization for this and there are meetings everywhere. You mentioned you’re concerned about them being defensive, and that makes sense. I was defensive, too. It’s terrifying to be in that place, and also, alcoholism tends to make one pretty fucking edgy. You wondered if you should wait until the person reaches out to you, and I’ll tell you: the chance of that happening is so tiny it barely exists. I didn’t reach out to anyone until I was caught and my back was against the wall, and even then, I didn’t go to people in my family or close circle. I did however take their words of concern to an AA meeting. And meetings were perfect because I got to hear about other people’s struggle, not mine. The finger was not pointed at me, but I got to hear the truth about me, told by someone who’d knew exactly how I felt.

If and when you approach them, do it in person if possible. Read: this isn’t a good text convo. Be non-threatening, compassionate, and honest. Anything accusatory will shut them down immediately (which may well happen anyway, and that is okay). Express concern, open the door, and then let it go if they don’t walk in. Perhaps return at another time.

This all of course assumes the person is not at the intervention stage. If you feel they need that type of help, consult an expert.

The last point I’ll make at the risk of telling you what you already well know is: this is serious. So very, very serious. Whatever concerns you or others have about the reaction you’ll get pale in comparison to the danger they’re likely already in. This may sound dramatic, but I assure you it’s not. I should have died so many times. I know at least ten people who’ve died this spring and summer alone – people who had been sober (some for a long time) and went back out because their heads convinced them they were safe to drink. One slipped on a staircase in a blackout and hit her head (I fell all the time), a few committed suicide, another died of health complications related to drinking (the autopsy probably didn’t mention that), another smashed into a concrete wall driving drunk.

I don’t say these things because you should use scare tactics. Scare tactics don’t work. I say these things so you know you’re not being dramatic. Your concerns are warranted. You should have the conversation.

If someone came to me several years ago and expressed concern I’d have pointed to all the things in my life that were working – and there were many – and assured them I was fine, just under a lot of stress, that I probably needed to be more mindful about drinking, yes, and that I would. I’d also file their words alongside all the other secret fears I had about my drinking. Point is, it would’ve mattered, even if it didn’t get me to stop. And that’s the thing: nobody and nothing can force someone to stop. But you can express honest, compassionate concern. You can show your seriousness by not drinking with them or around them and telling them why. You can talk to experts and read and absorb as much information as possible to understand what they’re facing and how best to support them. You can offer to go to a meeting with them. You can love them hard and understand they are sick, not morally flawed. And then you can send them light and love whenever you think of them and get angry, sick with worry, or afraid.

I wish you love and luck in the conversation, CFM. These things happen one moment, word, conversation at a time, and you really can’t screw it up. Our intent does matter quite a lot, even if it doesn’t come out pretty or lead to the desired outcome. Just show up and do the best you can. Above all else, show up.

Laura McKowen, the author of We Are The Luckiest: The Surprising Magic of a Sober Life writes powerfully and honestly on her blog. This article first appeared on her previous blog, I Fly At Night.